The Site of My Scholarship--History of O'Neill and Me

This is the site of my scholarship, or I could call it The Situation of My Scholarship in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night at Tao House.

And so this is the site of my scholarship.

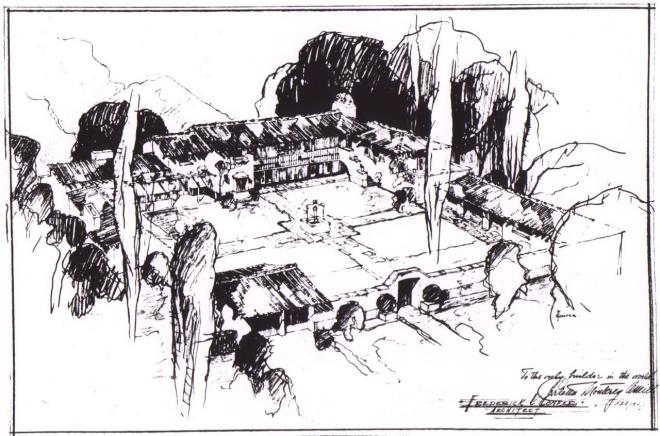

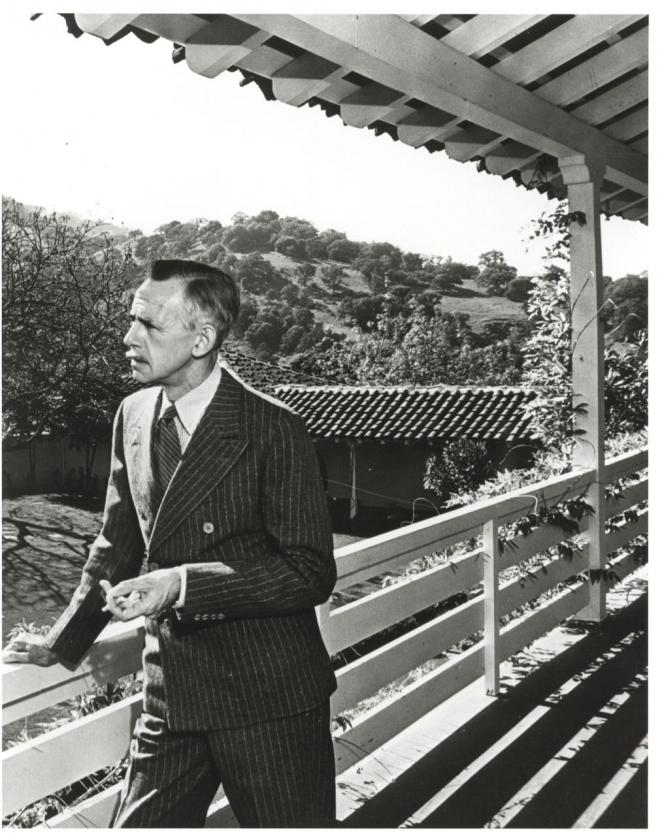

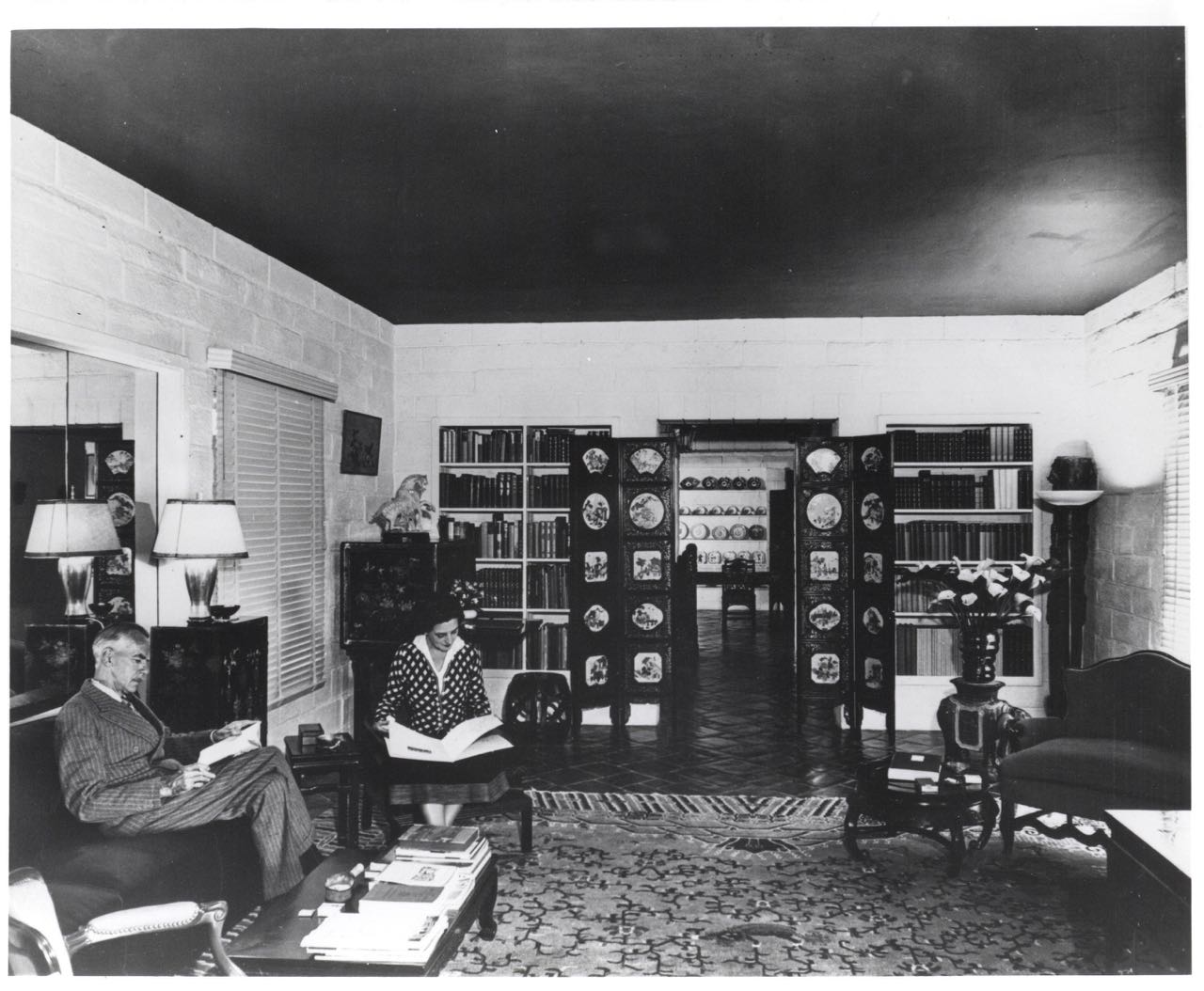

It’s a nice-enough house, and it has performed well on the real estate market twice. A realtor would describe it as a four bedroom, three-and-a-half bathroom, Spanish colonial house with 360 degrees of beautiful views of the Las Trampas Wilderness Area, an hour east of San Francisco. Large living room, family room, dining room, and tons of closet and storage space. Two-car garage. A gorgeous walled-in garden courtyard leads to three separate patio areas (“Entertain your friends!”), while a stunning fourth patio commands a sweeping view of the San Ramon Valley and Mt. Diablo. Separate fully equipped wing to house three servants. Secluded at the end of a long private road, on 158 acres of a former walnut ranch, with large barn, chicken coop, dedicated water supply, and a swimming pool with fully equipped changing houses, this property has endless possibilities for development. In today’s market, purely as a piece of property, it might sell for fifteen to twenty million dollars. The second and last time it was sold, the purchaser was the NPS, which has maintained it as a historic site since the 1970s. They were persuaded by a group of O’Neill scholars and local enthusiasts, who formed the Eugene O'Neill Foundation, that the place where this leading American playwright wrote The Iceman Cometh, Long Day's Journey Into Night, A Touch of the Poet, Hughie, and A Moon for the Misbegotten should be restored as much as possible to its original state and preserved for history. You can take a guided tour and be right there.

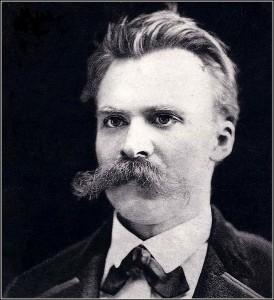

l. The former Barrett House Hotel, where O'Neill was born; it was on Longacre Square, now Times Square

r. Plaque on the site, next to a Starbuck's

—How does a play, a story, which is a knowing, first come into your knowing? It seems kind of personal, and it surely is, but that initiating moment—in place and time—is inevitably a site of your scholarship.

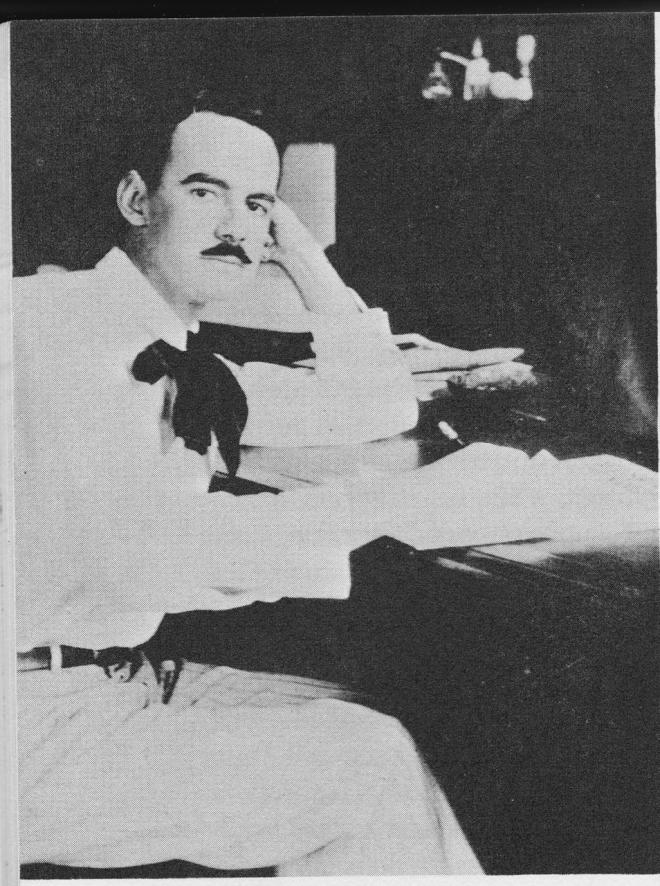

And so this is a site of my scholarship, the house in Ohio where I grew artlessly to the age of 14. Then I read O’Neill’s play, and it changed me. Fortunately, half a century later I can say that I came to this more proximate but not more intimate site of my scholarship, UCSB, in California, in a way that incidentally permits me to go back there to my own family history, just as O’Neill came to California in a way that enabled him to go back here--Monte Cristo Cottage.

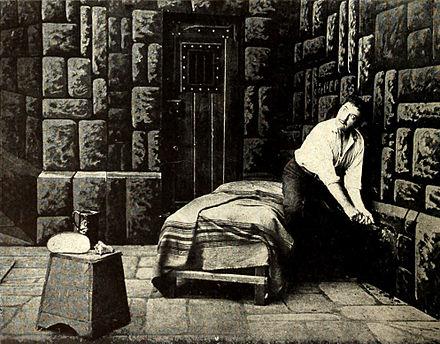

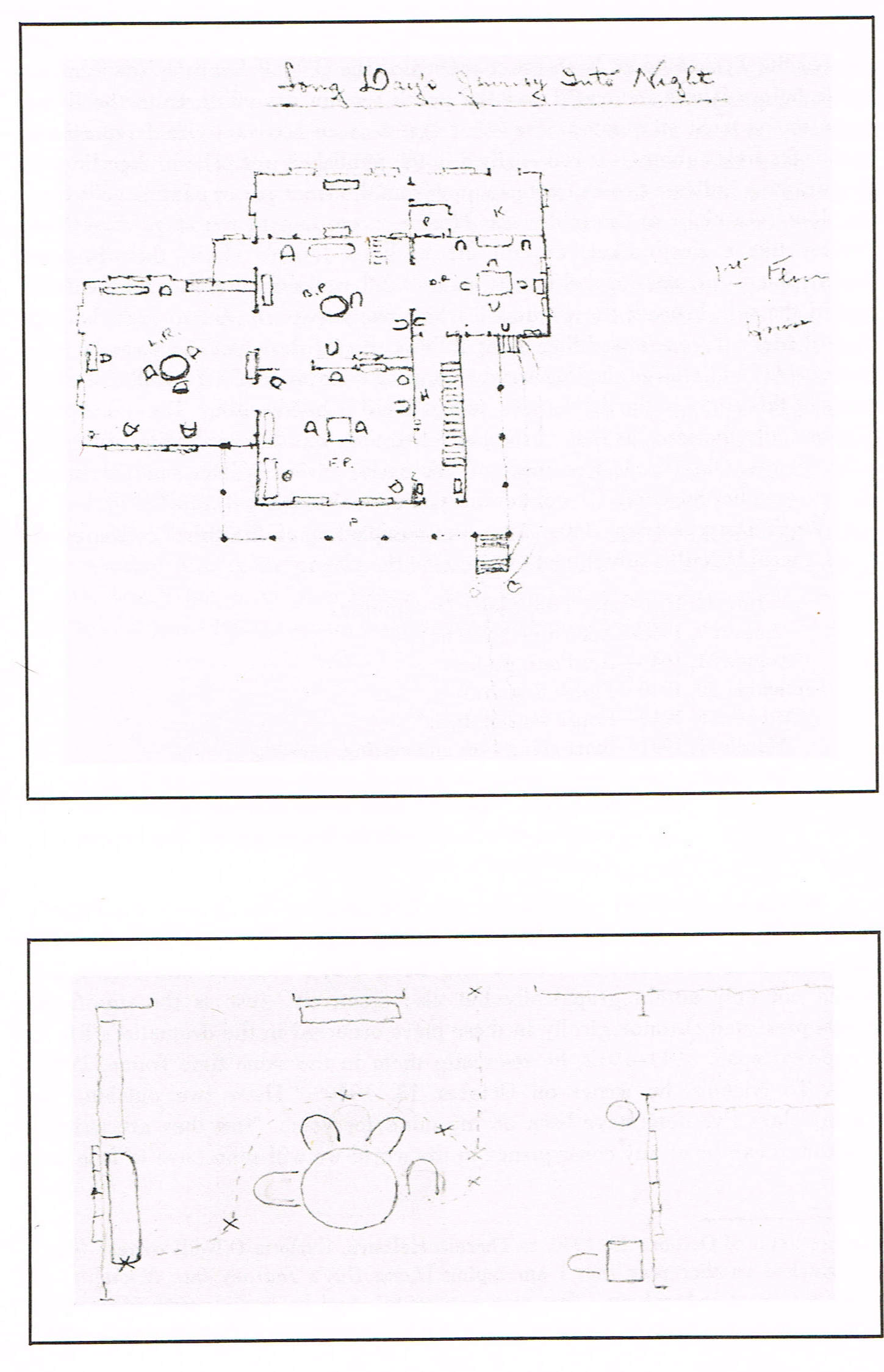

O’Neill drew from memory this floorplan of the house you just saw, and it’s quite correct, but here he gives it the title of his play. This drawing is the opposite of a mise en scène or stage set. It’s the topos from which he drew the story. It’s the house of his father, named for his famous play, but now with a new title—Long Day’s Journey Into Night. This is the living room of that remembered house, which is also a national historic site, currently maintained by the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center. And O’Neill created the drawing of that room in a house that also has a title, Tao House.

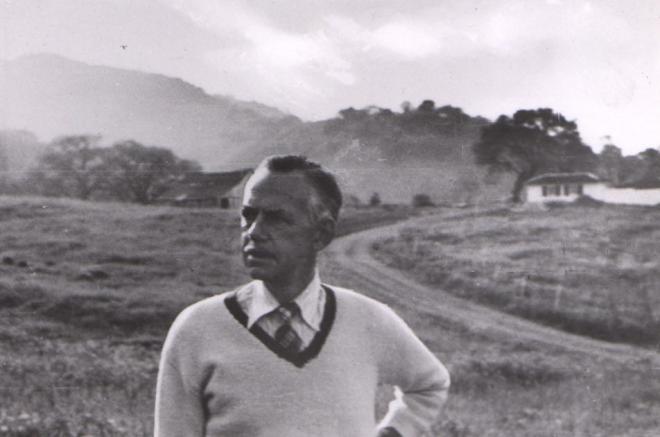

l. view toward Mt. Diablo

r. view toward courtyard; the barn in the distance

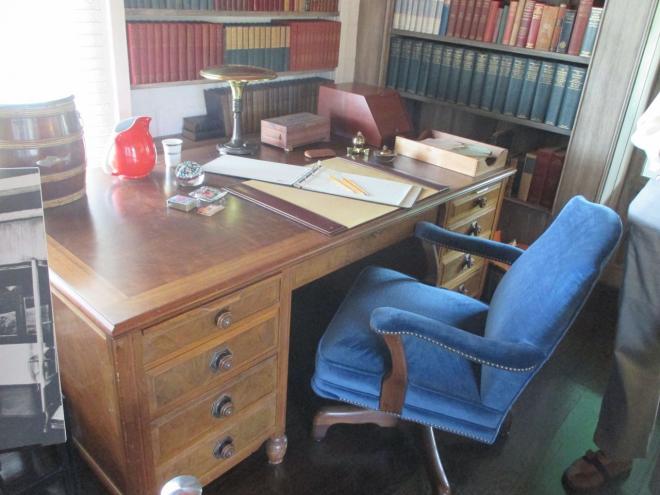

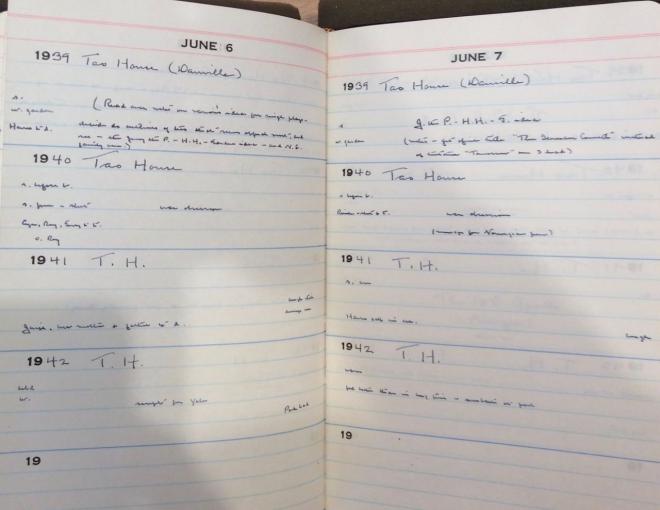

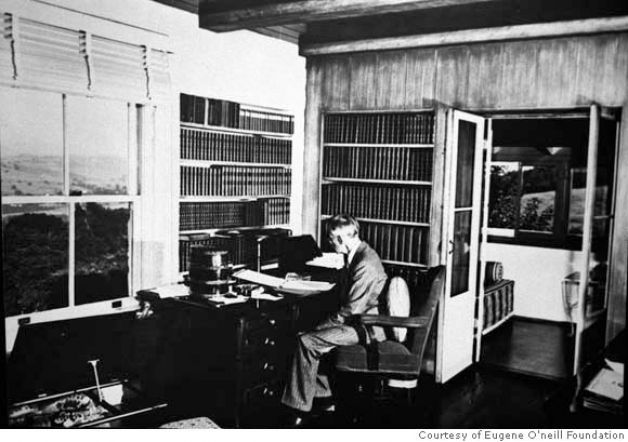

In writing Long Day's Journey, O’Neill brings the immanent past to the projected future, private experience to public recognition. His impulse to withhold the play from publication until long after his death is a sign of how this writing is not meant to be taken as an assertion or imposition—it’s not motivated by those “unnatural passions and desires,” such as fame, wealth, dominance. In a sense, this writing is neither active nor passive. The material of the past, in the form of memory, passes through him to become the scene of the future play to be acted and read. But even that is too dualistic to express the tao of it. What is present in him of the past flows into what is present of the future performance, which is an evocation of the past, which ends and yet does not end, which begins and yet has already begun. The play is, in that sense, an expression of the wu wei. O’Neill’s study at Tao House was the site where that knowing could flow. The play comes to know by being at home, and my project has been a quest to know that site.

Much of my book is about how Tao House came to be created as the place where that flow was possible, if only for a short time. The home made way for the play.

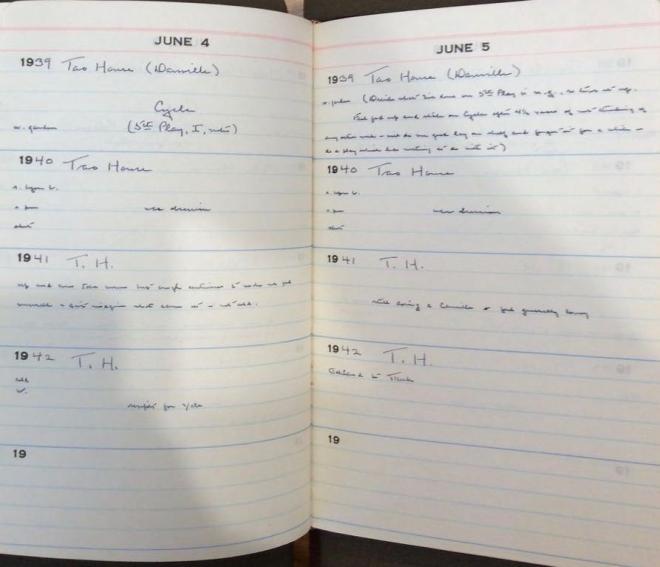

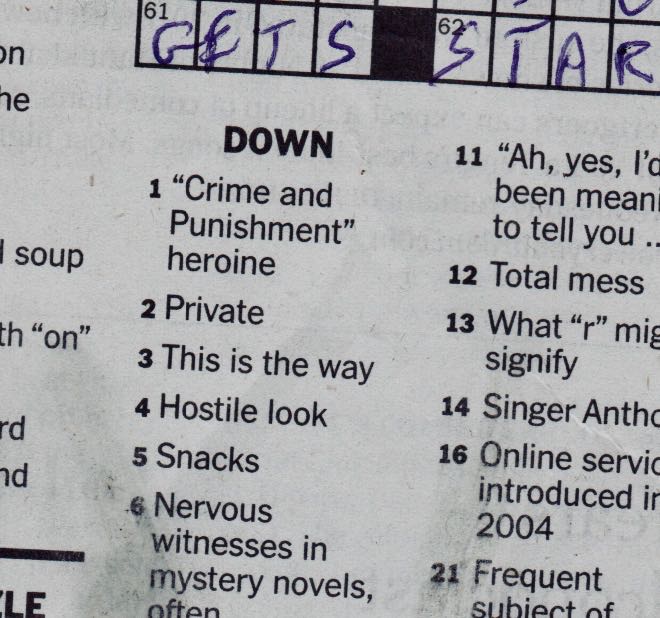

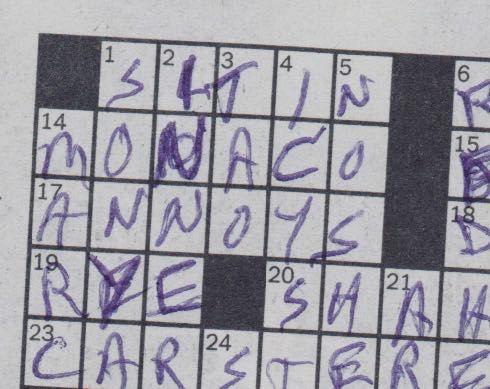

Look at 3 down.

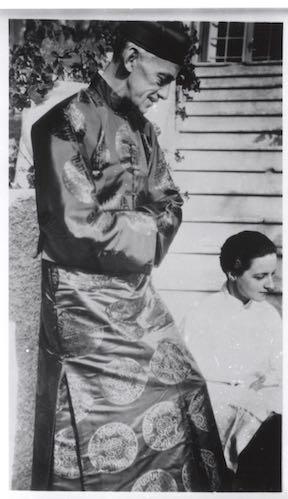

l. The "Trunk Room"--storage for Louis Vuitton trunks; now used for artist-in-residency office

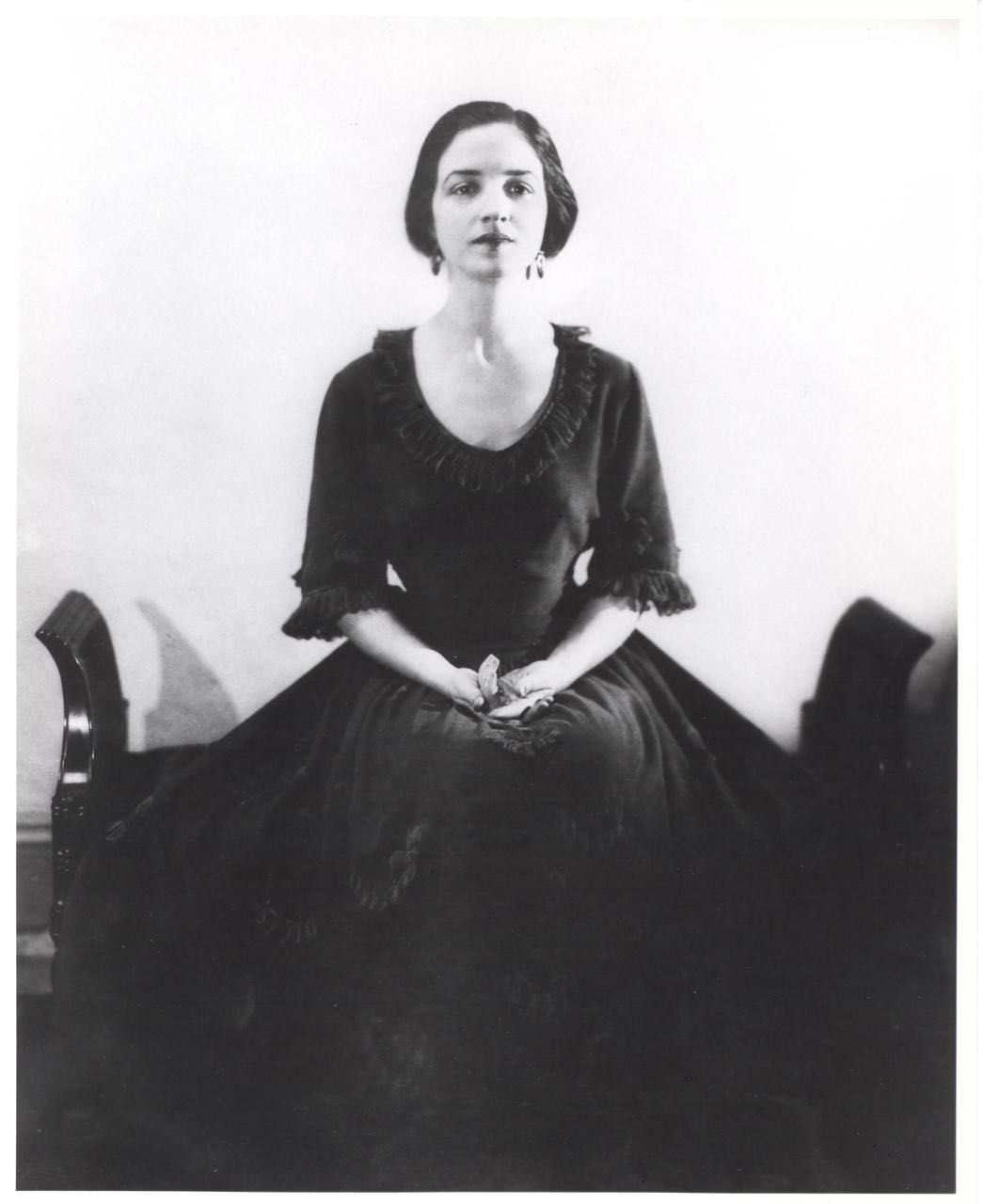

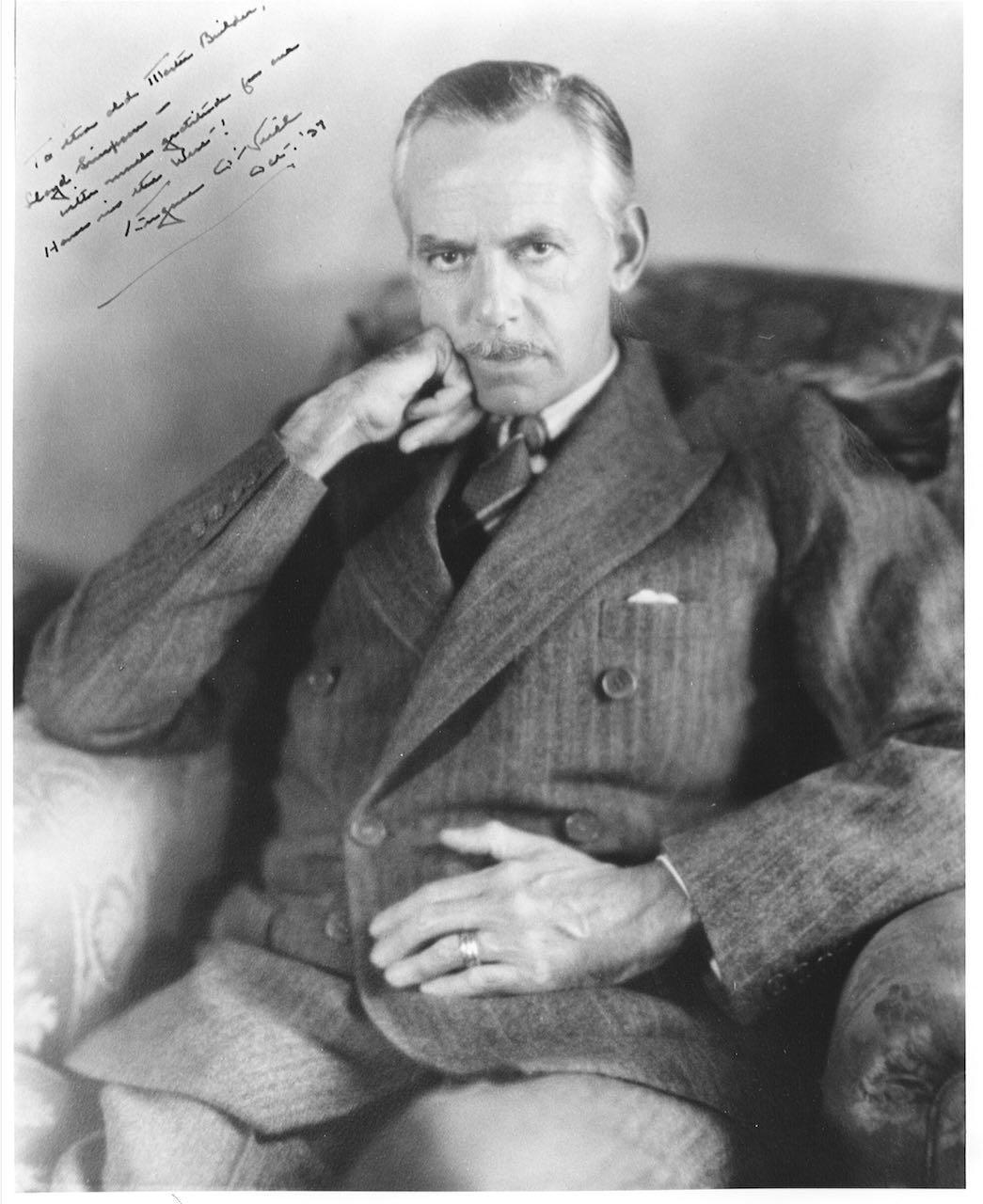

r. Gene and Carlotta in the courtyard, 1941

Yale University Press editions

A contrast in studies--O'Neill's and mine.

l. Trunk Room office--with my mess on the desk.

r. view from inside the office, looking at guest room; O'Neill's study above.

l. barn from the house.

r. house from the barn.